So you want to be a Genie? Here you are, taking your first baby steps on the path to finding out how to research your Family Tree and just so that we get our terminology right, people like us are called genealogists or family historians but for our purposes, we are going to stick to Genie for short.

Your reasons for embarking on this mission might differ greatly to mine but I can assure you that once you start you will want to continue, even if the only thing you ever wanted in the first place was an Ancestral Visa or to prove distant kinship to the Duke of Edinburgh.

Right from the outset I must warn you that it won’t be a walk in the park. In fact you will have to tone up those mental muscles and brush up on your sleuthing powers to be able to sidestep the many obstacles you will encounter along the way. Having said that, I must also say that you are in for a lot of fun and a roller coaster ride through history that will leave you gasping for breath. So get out that notebook, sharpen your pencil and let’s take the first steps together.

Where to start?

Contrary to everything your parents and teachers ever taught you, you do not start at the beginning! Yep, you read that correctly- never ever start at the beginning or, more specifically, never start from the earliest ancestor you can find!! You start at the end, with the last little twig on your family tree, YOURSELF.

The advantage of being stone last for a change is that you can work backwards from the known to the unknown. You know the names of your parents – there, you’ve already gone back one generation! You will also probably know the names of your grandparents and so on. With this in mind we are now going to do a little artwork. (This is where the notebook and sharpened pencil I warned you about earlier comes in handy). You are going to draw your first rough family tree.

Like this:

You carry on filling in names, using this format – remembering to include maiden names, dates of birth, marriage and death, where known, until you run out of them. It doesn’t matter if you have a few dates wrong here and there. If you are not quite sure when Grandpa and Grandma got married or when one of them ‘crossed over’ – no sweat, you can find that out later. Just get it down on paper. Drawing a rough tree gives you perspective and it is easier to see who’s who in the zoo.

The Thin Red Line

A really tough decision will present itself at this stage of the proceedings. Now is the time to choose which line you want to research first. Will it be Dad’s side of the family or Mom’s and even tougher still – will it be Dad’s paternal line (Dad’s Dad) or maternal line (Dad’s Mom)? It is important to make this choice and not rush headlong into researching everything at once. You will only get bogged down and downright confused. As you go along you will come across things that pertain to the other lines and it is important to jot down your sources, but don’t get sidetracked. (me with my big mouth – this is one of the hardest things about genealogy for me. It’s just too tempting.)

Once you have got your framework down, you are ready to progress to the next stage and this is a really fun part of Genie research because you get to go on a treasure hunt.

The X Files

You know that feeling when you go through the pockets of a seldom worn jacket and you find a wad of money you’d forgotten there? Well, the feeling is the same when you start going through old letters and photographs (the ones that your ancestors forgot to write on and you could now just die of frustration for wanting to know who the people in the photos are !!!!). Then there’s the old biscuit tin with family memorabilia in it like those old Union Castle ship’s tickets and menus, the wedding invitations and school reports. A diary would be like finding the Rosetta Stone, the ultimate treasure trove of information on your family – names, places, dates, juicy scandal…but I digress. This is the stuff Genies’ dreams are made of. All these goodies contain valuable clues about your ancestors – where they went to school, whether they were in the armed forces, where they traveled, who their friends were and the things that were important to them. This is the stuff that puts them in their context in history and breathes life back into the bare bones of genealogical data. So go and look in the attic or in that old suitcase at the top of your cupboard and sift through the remnants of your ancestors’ lives. Be careful to preserve the information in context. Don’t mix up your material or get photos muddled up with family members from other branches of your tree. If a photo isn’t marked, how do you know whether it’s from your Dad’s side of the family or Mom’s. So keep them together, as you found them, perhaps in envelopes, and label where you got it from etc. Later on we’ll talk more about keeping track of what you have done.

Driving (to) Miss Daisy

Whether you have a suitcase or a biscuit tin full of goodies or not, you will now have to do a bit of spit and polish on your diplomatic skills. Sooner or later you are going to have to approach living members of your family whom you have possibly not seen in years. You need to flip through that old address book and start calling some of them and don’t be offended if at first they don’t know who you are or the first thing they say is “Oh my Gosh – who died?”. Never mind too that there might be the small matter of the feud between your Mother and her distant cousins – it isn’t your feud after all. You must contact them and find out if they are willing to share information with you. They might have letters, photographs and maybe that diary we spoke of. All this can add info to your research efforts. Nine times out of ten they will only be too happy to share juicy tidbits with you and enjoy a sympathetic ear for an afternoon over tea and cucumber sandwiches. Remember to take notes. Relying on memory has its hazards and you will only kick yourself when you are hovering over the telephone, embarrassed because you have to ask for the information again.

Making a recording (video or audio) of an interview is an ideal way of capturing information. This is the ultimate ‘note taking’ exercise and is a wonderful way of capturing subtle inflections in the way Great Uncle Percy relates his life story. But I digress (again).

The purpose of all of this is to save you a lot of time and effort. Living relatives might have the very things you are looking for, namely birth or marriage certificates, details of military service, newspaper cuttings or death notices and they will often have personal background information on the individuals you are researching.

A word of warning here. In your enthusiasm to discover things, remember that your relatives (and many of those who remember long dead ancestors will probably be elderly) must be treated with the utmost respect and consideration. After all, you are invading their lives, forcing them to dredge up the past and making demands on them like “can I borrow these priceless photos to scan, Great Aunt?” when they haven’t a clue what scanning is. You tend to confuse and upset them and they might just banish you from their threshold. If they do not want to discuss certain things, leave it. Respect their privacy – it might be too upsetting or painful to recall.

Things your Mother (or Grandmother) never told you

If you are not prepared to be shocked, you might as well stop researching right now. I have done extensive research on behalf of many families and ALL of them have some kind of rattling going on in the closet. Some skeletons rattle louder than others but believe me every family has one. You can’t change the past. You can’t even ignore it because sooner or later someone will notice something and the closet door will begin to creak open. Once you start doing your forensic detective analysis of dates and people you often uncover things that make your eyebrows rise a notch or two. (they did things like that in 1865????). Maybe it is a child out of wedlock or a messy divorce or even a criminal record! Whatever it is, one thing’s for certain, the black sheep add contrast to the genealogical landscape and somehow things would be a bit boring without them.

Armed with this knowledge, just remember that some of your living relatives might still be ‘covering up’ certain indiscretions of the past and your evaluation of their version of the past must take this into account. Verify, verify, verify – which brings us to the next scenario.

Great Grandpa’s Shenanigans

Picture the scene…Great Grandpa was a Boer War hero. He was an officer in the army and was present at the Battle of Spioenkop and was personal escort to Lord Roberts when he …blah blah blah. Sounds great hey? My personal experience is, that in that whole scenario, there might be one tiny grain of truth, but that little grain often grows with the telling and Great Grandpa eventually ends up becoming this legendary, much decorated Boer War figure whose exploits will inspire films and documentaries. Be prepared to be disappointed with the family ‘legends’. The truth is often much more modest. Great Grandpa might well have been in the army and in the Boer War but he might have been a cook with the rank of Private and probably served with a regiment that was no where near Spioenkop. He probably also only clapped eyes on Lord Roberts whilst that august personage was riding through the field kitchen precincts. Don’t be disappointed – these are YOUR ancestors. You are where you are because of the choices they made and the experiences they had, however modest those might have been. Embrace them.

Good Will Hunting

I bet you never thought that looking at Death Notices and Wills would be fun. Try explaining this to a non-Genie and their expression changes to one of mild alarm. It is a bit off beat but these documents are the cornerstone of any genealogical research in South Africa and without them you would be hard-pressed to find concrete evidence of who the deceased’s parents were or how many children they had. This is going to be your next step – finding those Death Notices.

Why Death Notices?

The single most informative document in South African Genealogical research is the Death Notice, not to be confused with a death certificate, which is normally supplied by a medical practitioner and gives the cause of death along with some personal information. The Death Notice on the other hand, is a document which is usually filled in by a close relative such as the surviving spouse or one of the children and, in most cases, will give details of where the deceased was born, who the parents were, where and who they married, the names of all their children and whether they were majors or minors at the time of death, how old the deceased was at time of death, the deceased’s occupation, whether they left a will and whether they had moveable and/or immoveable property. A veritable treasure trove. This is where you need to concentrate your initial research.

Where do you find Death Notices?

Death Notices can either be found at the various National Archives repositories around the country or at the Master of the High Court (also known as the Master’s Office) depending on the date that the deceased estate file was filed. In Cape Town for example, all estate files prior to 1959 are housed at the Cape Town Archives in Roeland Street and 1959 to present day are at the Master’s Office. The other repositories have different date ranges for this and it would be wise to find out what these are before visiting.

The South African National Archives

There are six main repositories in the major centres in South Africa: Cape Town (Western Cape), Pretoria (Transvaal or Gauteng), Pietermaritzburg (KwaZuluNatal), Durban (KwaZuluNatal), Port Elizabeth (Eastern Cape) and Bloemfontein (Free State). Each repository is responsible for archiving all documentation relating to the province in which it is situated. Before you throw your hands in the air wondering how on earth you are going to find out which repository to search, there is light at the end of the tunnel and it is not a train coming. The National Archives has a free online database, which you can search to see whether there is any material on your ancestors. You can even visit the Archives in your area and use their computers to surf the database for free. The database is called NAAIRS – rhymes with stairs (National Automated Archival Information Retrieval System – try saying that after your second glass of sherry). NAAIRS helps you to find material and identify the repository in which it is housed. Just when you thought you could not get luckier than this I must warn you that the content of the document is NOT viewable online but a short description of it is provided, together with the relevant dates and reference numbers – it looks like this:

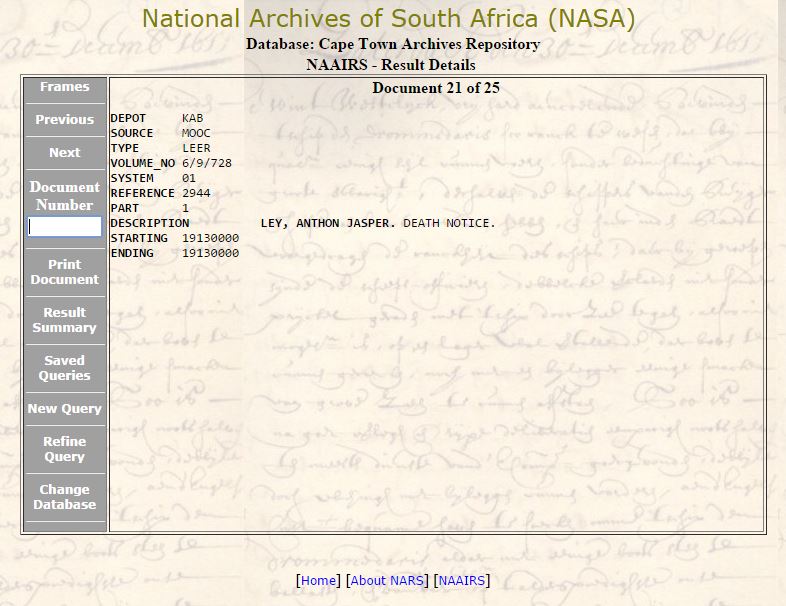

NAAIRS Death Notice Search for Anthon Jasper Ley 1913

In this example the Depot or Archive repository is KAB or Cape Town. The source or archive series is MOOC or Master’s Office/Orphan Chamber, Leer means file in Afrikaans and the document covers the period 1913, which is probably the year in which Anthon Jasper Ley’s deceased estate file was lodged. One must not make the mistake of assuming that this date is the date of death. Sometimes the estate file was lodge after the event. The date of death will however be indicated in the actual document.

Once you have found your document reference, you can request assistance from the staff at the repository itself by quoting the reference number or you can hire the services of a private researcher. Just follow the links on their website.

Remember that the National Archives has a wealth of material of which Death Notices are only a part. Later on when you are ready to flesh out the history of your South African ancestors you can broaden your search of NAAIRS to include other aspects such as what property they might have owned or what misdemeanours they committed. (Black sheep are well represented.)

Simple record keeping

Whenever I go through the earliest research into my own family tree, I could break out the sackcloth and ashes and weep at my poor record keeping. So ecstatic was I at finding information that I often omitted to write down exactly where I found it. The consequence of my stupidity was that a lot of that research had to be done again. Picture someone finding a nugget of gold in the desert. He rushes off to the nearest town to stake his claim and then discovers that he hasn’t got a clue how to explain where his ‘claim’ might be. He’d forgotten to write down the co-ordinates. Duh!!! You cannot write anything into your family history without being able to prove it. It’s just not scientific and will mean nothing to future generations.

Always try and get a copy of the documents – that means every death notice, baptism, marriage and burial relating to your family that you can lay your hands on. This is the best proof of authenticity that you will get. A photocopy, a digital photograph, even a hand written copy will do. Then…most important!!!! Make sure that you write down the place or repository where you found the document and where within that place the document is filed.

Using our example of the Death Notice for Anthon Jasper Ley above, you would note down KAB MOOC 6/9/728 reference no: 2944 LEY, Anthon Jasper Death Notice 1913 Cape Town Archives. You should also note the date that you accessed this document. All these details should be written onto any hard copies you make so that at a glance you know what’s going on.

Remember: Information minus source = hearsay, whilst Information plus source = fact

SUMMARY

- Draw a simple family tree, starting with yourself. Fill in as much as you know about your family using the format in the diagram shown.

- Choose which line you want to follow first.

- Contact living relatives and ask them to share information, photographs, certificates etc. Remember to approach these relatives with respect for their feelings and their possessions.

- Don’t take the family legends as gospel. Back them up with paperwork.

- Find the Death Notices for your ancestors using NAAIRS or by visiting your local Master’s Office.

- Always write down your sources in detail. You will end up repeating research if you don’t keep proper source records.