On the morning of Tuesday the 28th February 1832 some two hundred people witnessed a rather unusual public spectacle in the leafy little village of Wynberg just outside of Cape Town. It took place in front of the premises of William Moore the local baker and such was the nature of this event that those who witnessed it probably never forgot that morning for the rest of their lives. The occasion was a public execution.

To this end a gallows had been erected on an open space opposite 42 year old Moore’s home and business. Just before 9 am the prisoner, a slave by the name of Esau, was brought to the place of execution from the Cape Town jail and stood at the foot of the scaffolding. Here he would breathe his last in front of a sombre audience. But what events could possibly have led to this drastic end?

It all began 2 months earlier on Christmas Eve 1831. Esau, a 21 year old slave in the service of Jacob Pieter Cloete of the farm Groot Constantia, broke into a house belonging to Thomas Morris, a butcher in Wynberg. In the quietness of the darkened butchery he stole numerous items then left undetected. Not being content with his loot however, he also broke into the premises of William Moore the local baker. He entered the little shop, which was attached to Moore’s house, by removing a glass panel in a door and once inside proceeded to help himself to all sorts of things.

Awakened by a noise, Moore went to investigate and by the light of a lamp left burning in the shop, saw Esau, who tried to hide behind the counter. Moore wasn’t having any of that. He was a stoutly built man and tackled the young slave who panicked and grabbed two large, three pronged forks from the counter and stabbed Moore on the head, face, back and other parts of his body, severely injuring him.

By this time the noise had brought Moore’s twenty year old daughter onto the scene. (Although not named in any of the documentation pertaining to the incident, it would probably have been one of his eldest daughters, Mary Ann or Susan). She tried to help her father but the desperate slave attempted to stab her too. Somehow in the ensuing struggle he also bit her thumb, severely wounding her. Her cries for help swiftly brought other members of the household to the rescue and they eventually managed to overpower the youth. He was arrested and charged with: “the crime of shop breaking with Intent to Steal, the crime of Theft and the crime of Assault with Intent to Murder.” He was sent to the jail in Cape Town to await trial which took place on the 16th February 1832.

- Groot Constantia – photo by Sharon Warr 2015

Esau Goes on Trial

The jurors on duty that day were: Jacob Frederick Stober, Robert Logie, Christoffel Wolhutter, Simon Petrus Wolhutter, Leonard Frederick Anhuyzen, Richard Wrankmore, William Cooke, Arthur Goslett and Kennet de Kock, with magistrate Borcherds presiding.

During the course of the trial testimony revealed exactly what Esau had stolen that night. From the butcher’s shop “Esau did carry away 2 sheep, 6 pence in copper money, one phleme and 2 keys.” It is unclear from the court report whether the sheep were dead or alive but one thing is clear, he must have had help in getting those goods from the butcher’s premises. He either had some kind of vehicle, like a hand cart or trap, or he must have had accomplices. This is further supported by the list of things he stole or was preparing to steal from the baker’s house : “1 handkerchief, 16 papers of needles, 4 ounces of thread, three papers of pins, one farthing, 5 iron rings, 10 Rix dollars in copper coin of various denominations, one apron, 1 basket, 6 stone cans, 6 quarts of ginger beer, 1 whip, 4 cakes of Windsor soap, 5 knives and 20 loaves of bread.” By anyone’s reckoning that is a lot of merchandise.

Esau was asked to plead to the charges laid against him and pleaded ‘not guilty’. The jury however disagreed. They found him guilty and requested that the maximum sentence be handed down. When the judgement was read, the young man must have experienced terrible fear as the magistrate donned the black cap and uttered the dreaded words: “You are sentenced to be taken to the place from whence you came and thence at such time as His Excellency the Governor shall direct to a place of Execution and there to be hung by the neck until dead.” It was signed T H Bowles, registrar.

The sentence was harsh. But weighing heavily against Esau was the fact that he had repeatedly stabbed William Moore “by which he lost so much blood that he would have been overpowered and murdered by the prisoner but that his Daughter, a young woman about 20 years came to his aid”. Esau’s only defence was that he had no recollection of committing the crimes. He only remembered getting drunk at a canteen then waking up in prison.

Cloete Pleads for Clemency

All through the proceedings Jacob Pieter Cloete, Master of Groot Constantia, had sat in the court room and listened as the story unfolded. Esau had been born at the Cape around 1809 and had belonged to Jacob’s father Hendrik Cloete. In 1824 the boy was transferred to Jacob for a sum of 71 rix dollars and he had remained in his service ever since.

Groot Constantia – Photos by Sharon Warr 2015

Whether it was from kindness or whether it was motivated purely from a business point of view we will never know but on the 21st February Cloete wrote a letter to the Governor, Sir Lowry Cole, begging clemency for his slave.

He exhorted that “nothing could have been more remote from the mind of this slave than even an attempt to murder and that the mode of his resistance in every particular only evinced a desire to escape from apprehension and punishment…the Memorialist hopes that in the youth of the Prisoner and the further circumstances of the case there will be found ample grounds for Your Excellency to extend that mercy upon the unfortunate victim, the Prisoner…” The Protector of Slaves, Major George Rogers, himself a resident of Wynberg, also lodged an appeal for clemency.

But it was not to be. On the 25th of February, The Governor endorsed the sentence. “I approve of the execution for this sentence of Death passed upon the Prisoner Esau to take place at Wynberg on Tuesday 28th between the hours of 6 and 10 am.” And so, just three days later, Esau left the Cape Town Jail in the company of a guard and Mr. Marquard, a missionary and teacher who ministered to prisoners. On coming in sight of the scaffold in Wynberg he “did not evince the slightest emotion and said ‘were it three times as high he would not shed a tear”. He said he would die happy if his Master would only forgive him.

Esau took his leave of Jacob Cloete. He thanked him for the kindness he had always been shown and expressed his regret at the loss his master would suffer by his death. At 9 am the Reverend Mr. Faure read a solemn prayer at the foot of the scaffold. Esau seemed to listen intently and then it was time. The execution was carried out in front of two hundred spectators in the usually peaceful little village. Witnesses say he died without a struggle. His body was placed in a coffin some time later and taken away for burial.

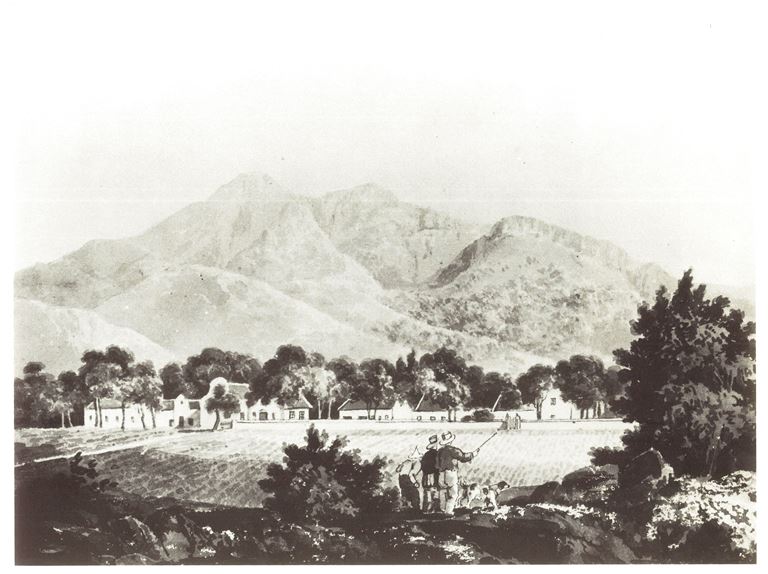

Groot Constantia – by Charles D’Oyly 1833

Esau’s sentence compared

The case caused much comment in Cape Town. It was said by “certain parties’ that the Court had previously shown leniency in similar cases and that Esau had been unjustly dealt with. The Governor also came under fire for sanctioning the execution. A correspondent for the South African Commercial Advertiser, who had written the original article on Esau’s execution, took these ‘parties’ to task in a scathing follow up article and said “it will excite no surprise among those who know the character of the parties by whom such infamous charges were laid before the public.” Could Jacob Cloete have been involved? He had after all lost a slave boy who had grown up under his very nose, not to mention a valuable asset. He would also have known about the drama that had unfolded only months before on his neighbour’s farm at Alphen.

Stabbing at Alphen

In that incident, on the 19th May 1831, a slave named January, then in the service of Thomas Frederick Dreyer, the owner of the farm Alphen, also in the district of Wynberg, was convicted of stabbing Dreyer in the abdomen with a knife. Dreyer was ‘grievously wounded.’ He also attacked and stabbed another slave named Frederick who came to Dreyer’s aid. January’s sentence was severe; 100 lashes on the bare back in public at Wynberg and thereafter to Robben Island for a period of 14 years with hard labour.

On the surface the cases were similar: both were slaves, both were convicted of assault with intent to murder (on two people) but the one got the death sentence and the other not. Jacob Cloete must have wondered. It can only be speculated that the Court considered the aggravating circumstances in Esau’s case, namely the violence, housebreaking and theft, very serious indeed. But possibly the most significant of all the aggravating circumstances was the attack on William Moore’s daughter, a defenseless young woman. That could not have sat well with the Jury.

Another aspect to this was the growing dissatisfaction of the residents of Wynberg with drunkenness and vagrancy in the area that led to petty theft, housebreaking and public indecency. Numerous memorials had been sent to the Governor without much action. Sir Lowry Cole must have thought Esau’s case a fine opportunity to be seen to be cracking down on the problem. No doubt all of these strands came together to seal Esau’s fate.

In his annual report of 1832 Major Rogers, the Protector of Slaves begins the section dealing with Esau’s case thus:…“this was the most atrocious case”… and ends…”the Jury found [Esau] guilty of the whole charge and he was sentenced to be hung until dead which sentence was carried into execution in front of the house at which the acts, which had brought him to his untimely end, had taken place.”

Esau’s execution was no doubt spoken of for a long time at Groot Constantia. One wonders whether any of his presumed accomplices were fellow slaves there and if they kept the secret of their involvement to the end of their days. Certainly, if any others were involved, Esau went to his death protecting their identities.

And what of William Moore and his family? They would surely have wanted to erase the unpleasant and traumatic experience from their memories, but it is more than likely that every time they walked past that open space in front of their residence, they would have been confronted by the spectre of Esau on the gallows.

William Moore died just 4 years later in January 1836, aged 47, at his residence in Wynberg.

Moore Road, Wynberg – photo by Sharon Warr 2016

This is a great article. Thanks for a good read.

This article is very problematic.

Perhaps it would be helpful if you could explain why it is problematic.

This William Moore was an ancestor of mine.

Jacob Cloete is an ancestor of mine.

This article is very interesting because it is relating an incident that happened almost two hundred years ago on the streets of Wynberg, Cape Town. The incident may not have been pleasant, but it nevertheless took place. History is about factual events and whether politically correct or not, need to be told. Thank you for sharing this story.

Fantastic article.

What sources and reference materials are you using for this? It would help historical research if you could give the occasional footnote.

Thank you Gerhardt. Glad you enjoyed it and thanks for taking the time to say so. I consulted various documents at the National Archives in Cape Town including Colonial Office, Slave Office, Supreme Court proceedings and various newspaper articles (South African Commercial Advertiser). It is such an interesting story – very thought provoking.